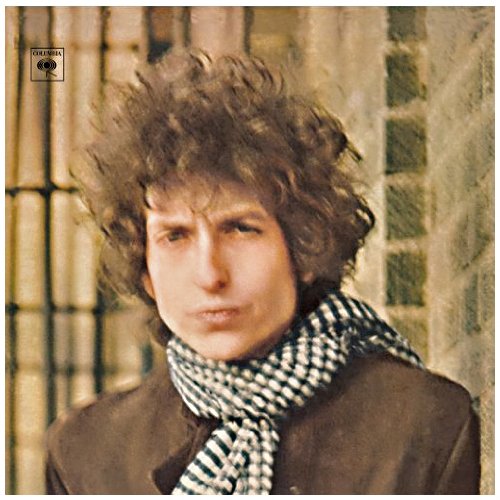

BLONDE ON BLONDE Album Review

In honor of Bob Dylan’s 75th birthday this week, I’ve decided to write a review of my favorite Dylan album, Blonde on Blonde. To declare with certainty that it’s my favorite is difficult—The Freewheelin Bob Dylan, Highway 61 Revisited, Bringing it All Back Home, and Blood on the Tracks all hold a place in my heart—but when I try to recall Dylan at his most honest, raw, and unapologetic, Blonde on Blonde is the first thing that comes to mind.

Dylan’s seventh studio album, released in 1966, was the first double album in rock history. After “going electric” in 1965, Dylan had faced harsh criticism from fans for drifting away from the folk movement and gravitating towards a more conventional rock ‘n’ roll sound. Blonde on Blonde was certainly a continuation of this stylistic trend: a few tracks are reminiscent of Dylan’s folk beginnings, but most show a strong rock or blues influence.

While the musical genius and lyrical creativity found in Blonde on Blonde are present in much of Dylan’s work, the album’s tone is completely unique. Dylan was always exceptionally mature as an artist in his twenties, but Blonde and Blonde just seems wiser, sincerer, and more self-aware than any album of his that preceded it.

The album’s opening track is the one you’re most likely to recognize. With its whimsical arrangement and memorable lyrics, “Rainy Day Women #12 and 35” climbed to No. 2 on the Billboard charts when it was first released as a single. “Pledging my time”, the second track, is just one of Blonde on Blonde’s several biting, frustrated, blues-inspired songs (“Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat”, “Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I’ll Go Mine)”, “Obviously Five Believers”, “Temporary like Achilles” ). If folk-driven ballads are more your speed, “Just Like A Woman” is a remarkably tender love song, arguably Dylan’s best. The haunting “Visions of Johanna” tells the story of a man striving for his idealized standard of love, while the narrative “Fourth Time Around” draws inspiration from the Beatles’ “Norwegian Wood” (movie buffs will recognize it from Cameron Crowe’s Vanilla Sky). “Absolutely Sweet Marie”, “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again”, and “I Want You” exude tired impatience, and “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)” explodes with the anguish of failed romance.

The album’s closing track, “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands”, shares a quality with many other Bob Dylan songs: it’s lyrically vague enough to take on a new meaning with each listen. While it doesn’t tell a coherent story, it conveys a distinct feeling of lovelorn weariness, and seems just as familiar as it is mysterious. This, in essence, is the magic of Bob Dylan’s music. Through its sharp wit and surreal inventiveness, his spirit shines as he gives a voice to frustration, loneliness, regret, and uncertainty. Lighthearted songs abound, but they are too honest to ever be purely joyful or uncomplicated. Dylan’s ability to simultaneously comfort and mystify audiences, all while staying true to his creative vision, marks him as a legend.